ALERT

March 05, 2024

Thailand: Key Similarities And Differences Between EU’S GDPR and Thailand’s PDPA

Thailand’s Personal Data Protection Act B.E. 2562 (A.D. 2019) (“PDPA”) came into full effect on 1st June 2022, a delay of three years from its enactment in May 2019. It heralds the country’s first consolidated personal data protection law. Prior to this, the right to privacy was recognized under the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand and some other specific legislation covering certain business sectors and for limited types of data. Since its enforcement, the PDPA has raised public awareness on collection and usage of personal data and gained much attention from businesses in general.

The PDPA sets forth standards and requirements for collection, use, disclosure, storage, and transfer of data relating to a natural person, which enable the identification of such person, whether directly or indirectly. It also establishes the Personal Data Protection Committee (“PDPC”), the governing authority with power and duties to ensure PDPA compliance and issue notifications, orders, and guidelines pursuant to the PDPA.

The enactment of the PDPA was approximately a year after the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Union (Regulation (EU) 2016/679) (“GDPR”) came into effect on 25th May 2018, signaling its firm stance on data privacy and security to the global arena.

Consequently, the PDPA has adopted many significant principles from the GDPR, e.g. its extraterritorial scope, consents, contract performance, legitimate interest and vital interest as legal basis, transparency of collection and use, and data transfer requirements. Notwithstanding these similar concepts, there are various key differences between the two due to some unique Thai perspectives in the law and its applications. This article aims to provide an overview of the key similarities and differences between the Thai PDPA and EU’s GDPR in various aspects.

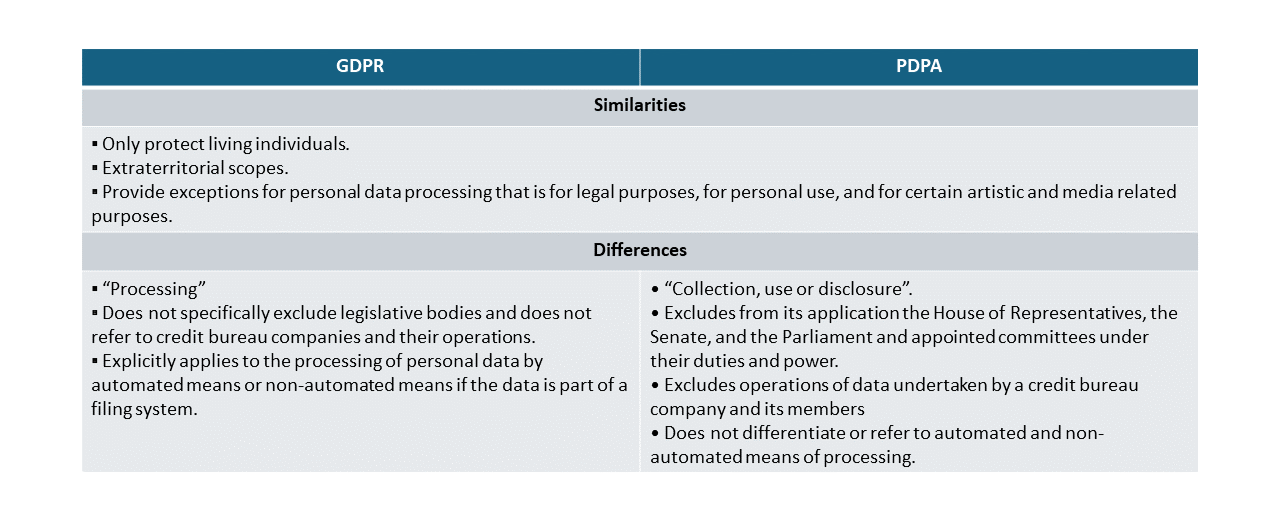

• Scope of Applicability

Both PDPA and GDPR only protect data of living individuals. It is expressly stated under Section 6 of the PDPA that ‘Personal Data’ does not include ‘the information of the deceased persons in particular’.

The PDPA has extraterritorial applicability in similar fashion as the GDPR. Not only does the Act apply to the collection, use or disclosure of personal data by a data controller or a data processor that is in Thailand, it also applies to those who are outside of Thailand, if their activities consist of offering goods or services to, or monitoring the behavior of, data subjects in Thailand.

The PDPA and GDPR have some common exceptions where the law does not apply. These include personal data processing for legal purposes, for personal use and for certain artistic and media related purposes.

On the other hand, there are some differences in their material scope of applicability. For instance, the GDPR applies to ‘processing’ of personal data with further explanation on what is considered as ‘processing’ while the PDPA uses the term ‘collection, use or disclosure’ with no explicit explanation or examples of actions.

The GDPR does not specifically exclude legislative bodies. Nor does it refer to credit bureau companies and their operations. On the other hand, the PDPA excludes from its application ‘the House of Representatives, the Senate, and the Parliament, including the committee appointed by the House of Representatives, the Senate, or the Parliament, which collect, use or disclose Personal Data in their consideration under the duties and power of the House of Representatives, the Senate, the Parliament or their committee, as the case may be’. The PDPA excludes ‘operations of data undertaken by a credit bureau company and its members, according to the law governing the operations of a credit bureau business’.

The GDPR applies to the processing of personal data by automated means or non-automated means if the data is part of a filing system whereas the PDPA is silent on these which implies that it is applicable to both processing means.

Table 1: Scope of Applicability

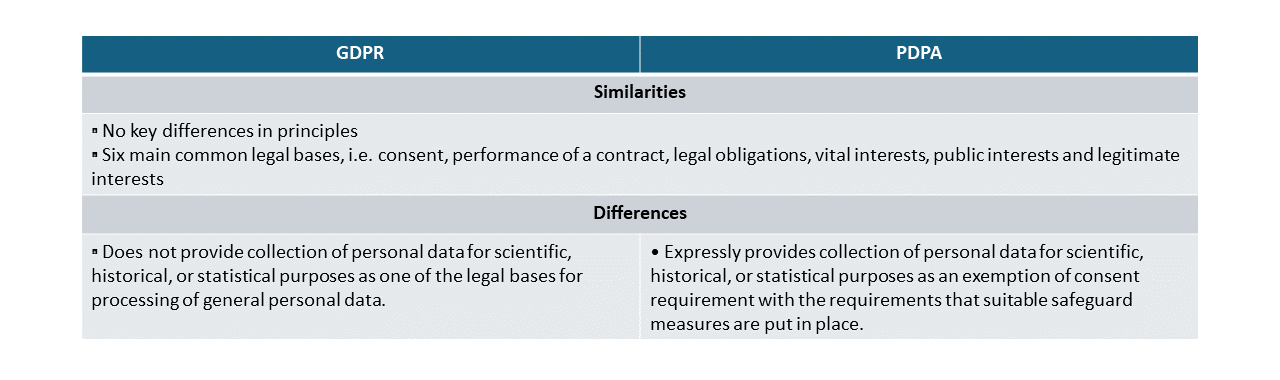

• Legal Basis

Both the PDPA and GDPR require a legal basis for processing personal data. There are six main common legal bases, i.e. consent, performance of a contract, legal obligations, vital interests, public interests and legitimate interests.

Besides the six common legal basis mentioned above, the PDPA also specifies another ground for collection of personal data which is a collection for scientific, historical, or statistical purposes, i.e. for the achievement of the purpose relating to the preparation of historical documents or the archives for public interest, or for the purpose relating to research or statistics, in which suitable measures to safeguard the data subject’s rights and freedoms are put in place.

On 28th December 2023, the PDPC issued the Notification on Appropriate Safeguards for Collection of Personal Data for purposes of research or statistics which will be effective on 7th April 2024. Under the Notification, the suitable safeguard measures required to be put in place are:-

1. Implementation of appropriate organizational, technical and physical measures to ensure that the collection of personal data is only as necessary and only for the purposes relating to research or statistics;

2. Implementation of appropriate security measures, considering level of risk to rights and freedoms of the data subjects;

3. Implementation of appropriate measures to control and monitor the collection of personal data according to relevant ethical standards and ensure that such collection is not in contrary to the laws;

4. Consideration on adopting pseudonymization or encryption measures.

Table 2: Legal Basis

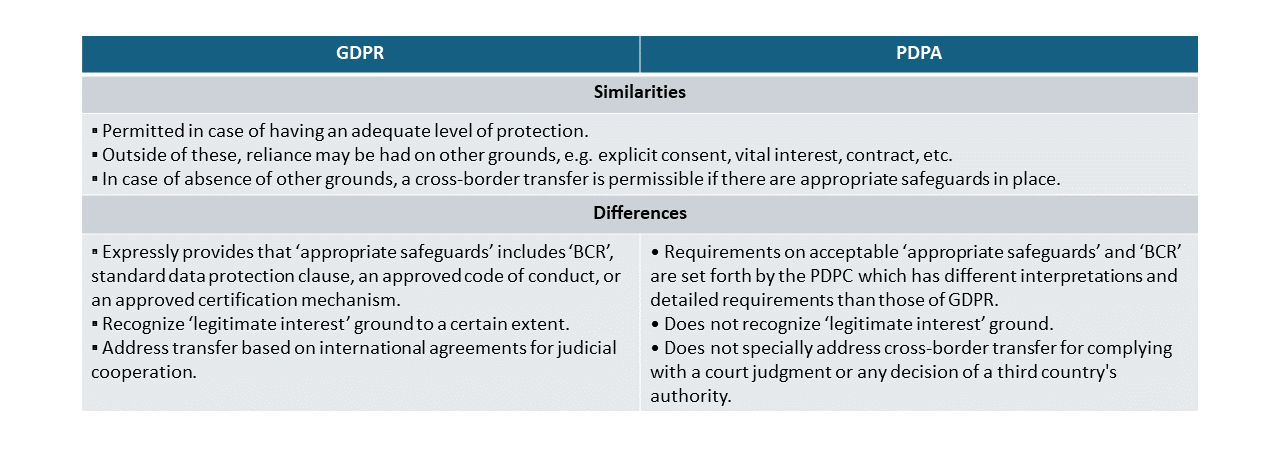

• Data Cross-Border Transfer

This issue is one of the major parts of both GDPR and PDPA. They provide restrictions, requirements, and exceptions to the cross-border transfer of personal data to a third country or international organization.

In similar manner, both the GDPR and PDPA permit cross-border transfer to destination countries or international organizations that have adequate level of protection, as determined by EU Commission for GDPR and in accordance with the rules prescribed by the PDPC for PDPA. Cross-border transfer to countries without adequate level of protection is also permissible under other grounds. They comprise consent of the data subject, performance of a contract, public interests, vital interests, and appropriate safeguards.

In respect of the appropriate safeguards, the GDPR provides guidance such as the Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs), the standard protection clauses, an approved Code of Conduct, or an approved certification mechanism.

The PDPA itself is silent on these‘ appropriate safeguards’ but leaves the room for PDPC to issue sub-regulations for requirements and conditions on these. To this end, on 25th December 2023, the PDPC issued the Notification on criteria of appropriate safeguards for cross-border transfer which will be effective on 24th March 2024. According to the Notification, the available appropriate safeguards are:-

(1) Having acceptable Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) which are in line with the conditions set forth by the PDPC with two distinct SCC models, i.e. (a) having specific provisions and contents as required under the Notification or (b) adopting one of foreign or international model accepted by the PDPC, such as ASEAN Model Contractual Clauses for Cross Border Data Flows or Standard Contractual Clauses issued under EU Regulation 2016/679 or GDPR;

(2) Obtaining certification that appropriate safeguards for cross-border transfer have been implemented, to be determined by the PDPC;

(3) Having a legally binding and enforceable instrument between Thailand and authorities of other countries.

For cross-border transfer of personal data among affiliated businesses or within the same group, the PDPC has also set forth in its Notification that having the Binding Corporate Rules can be a valid ground for cross-border transfer in this case, provided that such BCRs have been reviewed and approved by the PDPC.

It should be noted that the GDPR recognizes ‘legitimate interest’ as a ground for cross-border transfer to certain extent which is absent from the PDPA. Under the GDPR, a cross-border transfer is permissible if it is necessary for the purposes of compelling legitimate interests pursued by the data controller which are not overridden by the interests or rights and freedoms of the data subject, and the controller has assessed all the circumstances surrounding the data transfer and has on the basis of that assessment provided suitable safeguards with regard to the protection of personal data.

The PDPA, on the other hand, does not recognize ‘legitimate interest’ as a legal ground for cross-border transfer of personal data. One of the reasons may be that it involves too much of interpretation of laws and causes vulnerability to data security and rights and freedom of the data subject.

Furthermore, the GDPR specifies that a cross-border transfer is permissible based on international agreements for judicial cooperation whereas the PDPA does not specifically address cross-border transfer for complying with a court judgment or any decision of a third country’s authority.

Table 3: Data Cross-Border Transfer

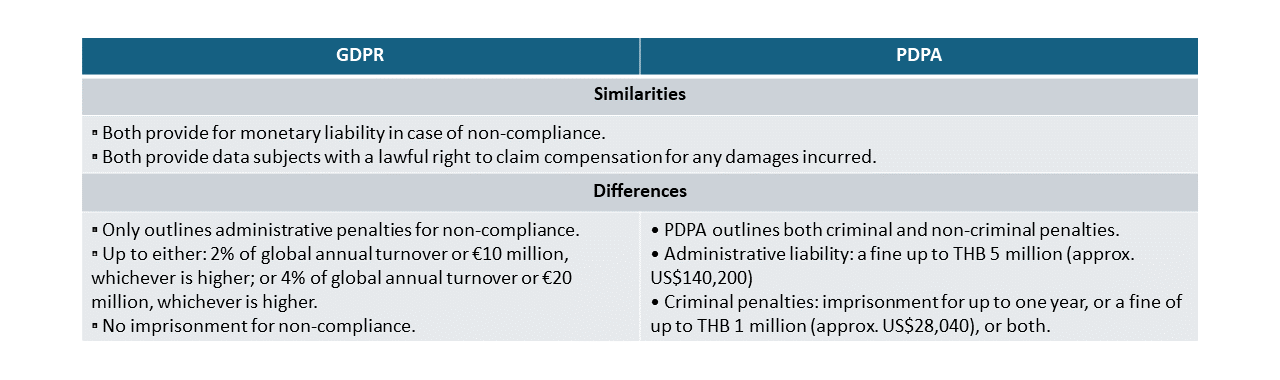

• Liabilities and Penalties

Both the GDPR and PDPA impose monetary penalties in cases of non-compliance, and both provide data subjects with a lawful right to claim compensation for any damages incurred.

Penalties for non-compliance with the GDPR have caused concerns to businesses even before the GDPR came into effect. There are two levels of GDPR violations – for the lower level violations, they could result in an administrative fine of up to €10 million, or 2% of the annual global turnover of the company of the preceding financial year, whichever is higher, and for the severe violations, they could result in an administrative fine of up to €20 million, or 4% of the annual global turnover of the company of the preceding financial year, whichever is higher.

For PDPA, besides civil liability for damages, the Act outlines both criminal liability and administrative liability for penalties. Failure to comply with the PDPA could result in administrative fines of up to THB 5 million (approx. US$140,200) and criminal penalties which include imprisonment for up to one year, or a fine of up to THB 1 million (approx. US$28,040), or both.

Table 4: Liabilities and Penalties

Since the PDPA became fully in force, the PDPC has been issuing several sub-regulations to fill the gaps and clarify some key provisions of the PDPA. The Office of PDPC has also been quite active in monitoring and investigating many data collection and usage activities including conducting investigations into some data controllers. According to PDPC’s statistics that are publicly available, the PDPC has issued more than 90 administrative orders requiring controllers and processors to comply with the PDPA, to take action, rectify issues and cease certain activities. Some have been warned for their noncompliance. As of 19th January 2024, the Office of PDPC has received around 394 complaints, most of which are relevant to online activities and social media.

We would like to emphasize here that although the PDPA has adopted many principles from the EU’s GDPR, there are several key differences between the two due to unique Thai perspectives in the law and its application. In this regard, in order to guarantee compliance with the PDPA and its sub-regulations, businesses should review and revisit their data-relevant activities and measures in place. Needless to say, compliance with the laws of other countries or even with the EU GDPR does not automatically ensure compliance with the Thai PDPA.

*If you have any questions or require any additional information, please contact our Partner,

Paramee Kerativitayanan, at paramee.k@zicoip.com or ZICO IP (ZICOlaw (Thailand) Limited).

Contributing Authors

Paramee Kerativitayanan

Partner

- IP, Law

- Bangkok, Thailand.

- +66 92 267 8777